Do you experience pain with throwing or swinging a racquet overhead? What about simple tasks such as bringing your arm through a jacket or reaching behind your back to do up a bra strap? Do you wake up in the night or have difficulty getting to sleep due to a throbbing pain in your shoulder?

Symptoms such as those above are consistent with Rotator Cuff Dysfunction. Rotator Cuff Dysfunction is one of the most common musculoskeletal injuries involving the shoulder. Although Rotator Cuff Dysfunction is quite common it will present differently with each individual. Factors such as past and current athletic/occupational demands as well as the duration, intensity, and frequency of symptoms can all contribute to the individuals pain complaint. This can be further complicated by secondary adaptative strategies that have been developed over time as well and psychosocial factors such as past negative experiences and poor expectations of recovery. The combination of all these factors lead to a unique pain presentation requiring an individualized treatment approach.

The good news is that with a proper and thorough assessment and well-developed treatment plan majority of individuals with Rotator Cuff Dysfunction will do very well with a conservative management plan consisting of education and guidance through a gradual graded strengthening program.

The goal of this article is to provide individuals with Rotator Cuff Dysfunction a resource of information related to the anatomy and pathology of Rotator Cuff Dysfunction as well as treatment strategies so that they can better manage and understand their condition.

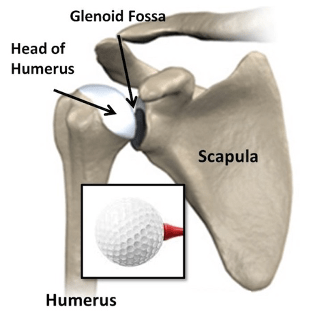

The Glenohumeral Joint

The glenohumeral joint (shoulder joint) is comprised of the scapula and humerus or more specifically the glenoid fossa of the scapula (small, pear shaped) and the humeral head (spherical, large). It is the articulation between the glenoid and humerus where the glenohumeral joint derives its name. The glenoid fossa is only ¼ the size of the head of the humerus, this allows for an incredible amount of mobility but a relative lack of boney stability (compared to the hip joint). You can think of this relationship similar to a golf ball sitting on a golf tee. To make up for this relative lack of boney stability the glenohumeral joint receives additional stability from soft tissue structures including the glenohumeral labrum, glenohumeral ligaments and rotator cuff muscles. The glenoid labrum is a fibrocartilaginous tissue that deepens the glenoid fossa by 50% and contributes to the control of humeral head translation. Stability of the shoulder can be significantly compromised if there is an injury to either the labrum (tear/avulsion) or glenoid (fracture- Hill-sachs/Bankart lesion / degenerative changes- osteoarthritis).

Glenohumeral ligaments add further stability to the glenohumeral joint. The generalized function of these ligaments is to provide passive restraint to limit extremes of motion, provide stability of the humeral head in the glenoid and guide the position of the shoulder during movement. These ligaments also play a vital role in shoulder proprioception (the body’s ability to perceive its own position in space). The main source of injury to the glenohumeral ligaments comes from trauma aka subluxation/dislocation of the shoulder. If not treated properly a shoulder dislocation can lead to ongoing laxity of the ligaments and poor proprioception resulting in chronic instability and recurrent shoulder dislocations.

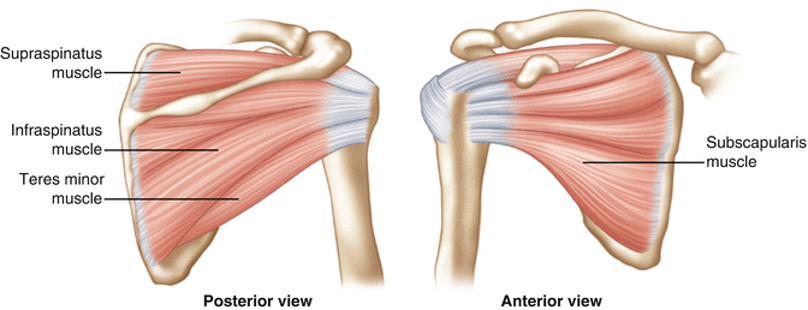

Muscular stability of the glenohumeral joint comes from the rotator cuff muscles. The rotator cuff muscles are comprised of a series of four muscles that attach to and around the glenohumeral joint; the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, subscapularis. The goal of the rotator cuff muscles is to work together to stabilize and securely hold the humeral head into the glenoid fossa aka they compress the humeral head into the glenoid. They also play an important role in depressing the humeral head in the glenohumeral joint and assist in movement of the shoulder joint. Injury/pathology of the rotator cuff muscles can lead to abnormal translation of the humeral head in the glenoid fossa leading to secondary irritation of surrounding structures in the glenohumeral joint. This is often referred to as Sub-Acromial or Rotator Cuff Impingement. We will discuss rotator cuff pathologies in greater detail next.

Rotator Cuff Dysfunction

As discussed above the main goals of the rotator cuff muscles are to centre/compress the head of the humerus in the glenoid fossa, depress the humeral head in the glenohumeral joint and assist in movement of the shoulder. It is important to note that although the rotator cuff muscles play an important role in shoulder movement, they are not the primary movers of the shoulder. Movement of the shoulder is performed predominantly by the bigger stronger muscles of the shoulder (deltoids, pec minor/major, lats, trapezius, biceps etc..).

The main pathologies involving the rotator cuff muscles are Rotator Cuff Tendinopathy and Rotator Cuff Tears (degenerative and acute). Both of these pathologies usually get characterized under the term Rotator Cuff Dysfunction and present with similar symptoms related to Rotator Cuff Impingement. Rotator cuff impingement is not a diagnosis but rather a secondary symptom related to rotator cuff tears/tendinopathies.

Rotator cuff impingement occurs when the rotator cuff tendons fail to depress the humeral head and compress it into the glenoid fossa. This leads to abnormal translation or movement of the humeral head during shoulder movement causing the humeral head to “impinge” on or irritate other structures within the glenohumeral joint i.e. tendons, ligaments, nerves, blood vessels etc.…

Rotator Cuff Tendinopathy

A tendon is a contractile tissue that connects muscle to bone. As a result tendons deal with a tremendous amount of load transfer from muscle to bone requiring the tendon to have a high capacity to load. Tendinopathies can be simplified as a complex cascade of poor biological changes to the structure of the tendon that has developed as a result of a poor load/capacity relationship i.e. load is greater than capacity. All tendons require a good load/capacity relationship, where capacity exceeds load demands. Tendons need a gradual exposure to load to get stronger and build up a load capacity. When the load exceeds capacity either acutely (all at once) or chronically (over time) the tendon will begin to fail and start developing poor biological adaptations in an attempt to meet load demands. An example of acute overload is a young thrower who has taken the offseason off of training and too quickly returned to a throwing program OR a middle-aged person that normally has minimal exposure to overhead activity then paints their ceilings. An example of chronic overload would be an electrician who is constantly exposed to overhead loading but does not compensate for this load demand with any tendon strengthening program therefore the load slowly creeps above capacity over time.

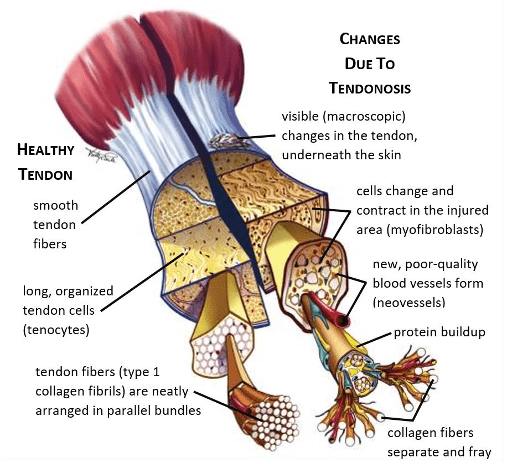

At the biological level a healthy tendon is comprised of many molecular structures including Type 1 collagen that are tightly bundled in a parallel linear fashion that optimizes load transfer. There is minimal nerve innervation and vascularity (blood vessels) to the tendon itself. In a dysfunctional tendon there is a breakdown and disarray of collagen fibres, and a proliferation (rapid growth) of large blood vessels and nerve endings with sensitivity to pain creating a reactive tissue. Proliferation of the tendon can develop over a period of 6 weeks and is it at its peak usually by 12 weeks, it can take up to 6-12 months to settle. This proliferation time period can help explain why a lot of people if not managed early can expect a longer overall prognosis and should be educated on the overall prognosis, the signs and symptoms of proliferation and proper treatment strategies.

Rotator Cuff Tears

Degenerative Tear

Tears in the rotator cuff tendons are not an uncommon finding in the asymptomatic shoulder of individuals with shoulder pain. Meaning we can not necessarily correlate rotator cuff tears on imaging with pain presentation. Due to the high load demands of the rotator cuff tendons small and even full tears of the rotator cuff tendon are likely to occur over time as a normal process of aging. These tears are mostly asymptomatic meaning that you can lead a quite functional life without shoulder pain in the presence of a rotator cuff tear.

When an individual experiences shoulder pain in the presence of a rotator cuff tear it is more likely that the pain source is coming from another structure in the glenohumeral joint as opposed to the tear itself. This pain source could be a tendinopathy/proliferation to another one of the rotator cuff tendons, shoulder instability, shoulder stiffness/contracture etc… A conservative management program of education, modifying activity, and gradually strengthening is advisable prior to any more invasive treatment options. The exception to this approach would a traumatic rotator cuff tear.

Acute Tear

An acute traumatic tear usually occurs in individuals over 35 years old. The mostly likely mechanism is a fall onto an outstretched arm or fall while grabbing onto an object to stop the fall. Acute traumatic tears usually do not have as good of a prognosis as degenerative rotator cuff tears and therefore should have imaging and an orthopedic consult with a surgeon to determine best treatment options.

Signs and Symptoms of Rotator Cuff Dysfunction

Signs and symptoms of Rotator Cuff Dysfunction can vary from person to person. It is important when being assessed for Rotator Cuff Dysfunction to have a thorough subjective history and physical assessment as it can help develop treatment strategies, prognosis, and identify any other potential diagnosis.

Signs and symptoms of Rotator Cuff Dysfunction may include the following:

- Dull aching pain in the lateral upper arm, anterior shoulder or posterior shoulder

- Painful catches through range of motion – overhead activities i.e. throwing, racquet sports

- Pain with putting arm into coat/shirt

- Pain with driving/leaning on the elbow or outstretched hand

- Pain at rest, frequently worse at night (increased vascular proliferation at night)

Prognosis

It is an important part of the treatment plan to develop a realistic prognosis of recovery. Prognosis will be influenced by a multitude of factors including but not limited to the duration of symptoms, load demands of the individual (and the ability to modify those load demands), age, stress levels, sleep quality, and personal beliefs of recovery. It is believed that rotator cuff dysfunction when managed effectively can take 4-6 months to recover, poorer prognosis can be up to 12 months.

Treatment

The goal of a conservative management plan of Rotator Cuff Dysfunction is to first use strategies to settle the pain symptoms and then begin a gradually graded strengthening program to build up load capacity.

Early Phase

The goal of early phase management is to settle pain symptoms. This is primarily done with a thorough education and answering any concerns regarding Rotator Cuff Dysfunction, identifying loading errors, modifying load as able, and initiating motor control exercises.

Manual therapy techniques such as soft tissue release and joint mobilizations can also be effective during this phase for pain modulation but should be used on a short-term basis. Taping techniques can be effective as they assist with motor control training. Electrotherapy modalities can also be used in this phase with the understanding that the goal is pain modulation and benefits will be temporary.

Exercise ideas for early phase rehab include: self-massage with lacrosse ball and motor control exercises for humeral head placement/scapular rotation.

- Tissue release with Lacrosse Ball – move lacrosse ball throughout the back of the shoulder blade and up towards the neck. Ideally looking for tender spots in the muscles. Once a tender spot is identified hold pressure for 30-60 seconds focusing on slow controlled breathing or until tenderness starts to dissipate. Spend 3-5 minutes, 2x/day.

- Scapular Retraction Motor Control – lift your shoulder blade “up, back, and halfway down”. The goal is to slowly retrain the position of the shoulder blade. This can also be optimized by the use of a theraband wrapped around the shoulder. Hold 10-20s, 10×3, 3-4x/day

Early-Mid Phase

Once night pain and resting pain has settled a gradual graded strengthening program can be introduced.

Introduction to loading will differ from person to person depending on their capacity to load. It is best to be advised by a Physiotherapist to determine what level of load is appropriate. Often case isometric loading is the first type of load to be initiated. This involves statically loading the tendon without any shortening or lengthening of the tendon (no range of motion).

Following successful isometric loading. Tendon loading through range can be initiated. At this stage range should be kept below shoulder height and gradually progressed to increased levels of shoulder elevation. The greater degree of elevation the more demand will be placed on the rotator cuff muscles to keep the humerus compressed/centred in the glenohumeral joint.

Examples of Early-Mid Phase exercises are below:

- Isometric External Rotation Walkout – start with your elbow bent to 90 degrees and and forearm perpendicular to your stomach. Start with tension in the theraband. Take 1-2 big steps away from theraband so tension increases. Do not allow your forearm position to move and focus on the muscle effort coming from the back of your shoulder. Hold 5-10s, 10×3.

- Heavy Slow Resistance External Rotation – start with elbow bent to 90 degrees and forearm perpendicular to stomach. Start with a moderate to heavy tension in theraband as tolerated. Rotate forearm away from body holding for 3 seconds at end range. Focus on muscle effort coming from back of your shoulder. Hold 3-5 seconds, 10×3 or to muscle fatigue.

** add a towel or pillow between your elbow and ribs for better activation from posterior cuff

- Isometric External Rotation w. Uppercut – start with elbow bent to 90 degrees and forearm perpendicular to chest. Start with moderate tension in band. Maintain elbow bent to 90 degrees and forearm perpendicular as you make an uppercut motion to ceiling. Hold 3 seconds, 10×3 or to muscle fatigue.

- Low Row – start with moderate to heavy tension in theraband. Pull band back into row position. Can be progressed by keeping elbows extended. 3-5s hold, 10×3 or to muscle fatigue.

- Reverse Fly – start with elbows locked in near full extension. Pull arms out to side in reverse fly. Focus on muscle effort coming from between the shoulder blades. Hold 3-5 seconds, 10×3 or to muscle fatigue.

Mid-Late Phase

Mid-late phase rehab involves strengthening the rotator cuff muscles in greater degrees of elevation and eventually strengthening into more global movements and sport/occupation specific demands.

Examples of Mid-Late Phase exercises are below:

- Shoulder External Rotation at 90 Degrees – start with elbow bent to 90 degrees and shoulder at a 90 degree angle. It is important to activate the core during this exercises so you do not cheat with thoracic extension. Hold 3-5 seconds, 10×3 or to muscle fatigue.

- Shoulder External Rotation + Shoulder Press – start with elbow bent to 90 degrees and shoulder at 90 degree angle. Activate core. Press up to ceiling maintaining forearm perpendicular to floor. 10×3 or to muscle fatigue.

If you would like more information you can contact david@modernphysio.ca